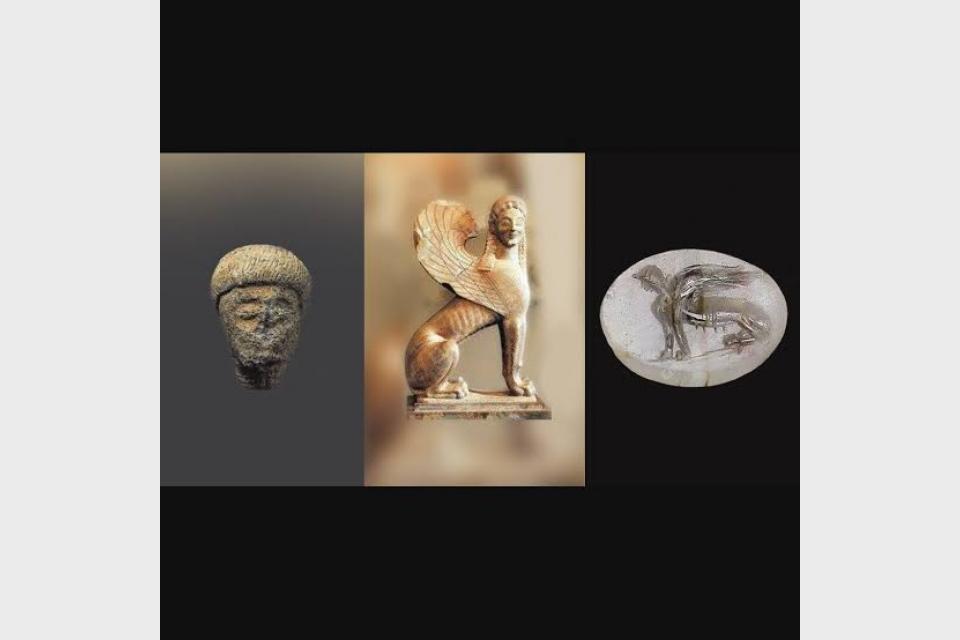

.What was a seal ring with the carving of the Sphinx, which looks similar to the one worn by the Roman Emperor Augustus Caesar about 2,000 years ago, doing at Pattanam, a sleepy hamlet, 25 kilometres north of Kochi in Kerala? A seal, part of a ring, was retrieved on April 25, 2020, a couple of days after the lifting of the national and State-level COVID-19 lockdowns, when excavations were marginally restarted at Pattanam by the PAMA Institute for the Advancement of Transdisciplinary Archaeological Sciences. The trench, named PT 20 XLV, was located in the backyard of the kitchen-shed of Sukumaran and his five sisters at the northern sector of the Pattanam archaeological mound. The tiny, oval-shaped seal, with a length of 1.2 cm, width of .2 cm and thickness of .1 + cm, was found at a depth of 115 cm, where it must have remained for centuries while life flowed on and empires and emperors vanished into the mists of history. Pravitha P.A., a student intern of the excavation team, picked it up from the wire-mesh net while sieving the soil from locus 5.

Pattanam is assumed to be the legendary port of Muziris or Muciri Pattinam, which finds mention in ancient Greek and Roman sources as well as in the Sangam literature dating back to the centuries before the Common Era. It is from these references that we know Muziris was a centre for a booming trade in goods that linked the indigenous worlds of the Graeco-Romans, the Egyptians, the West Asians, the Africans, the South Arabians, the Indians and the Chinese. The Pattanam 2020 findings, along with the 2006–16 excavation and post-excavation studies of the same site, reconfirm the intense maritime commercial, technological and cultural exchanges between Eastern Mediterranean and ancient Tamilakam.

But who could have made the ring with the Sphinx, and how did it end up at Pattanam? Did one of the traders or perhaps an emissary of the emperor bring it with him or her? Or was it made in Pattanam itself, especially since there is evidence of people working there with numerous precious stones such as agate, amethyst, beryl, carnelian, chert, garnet, onyx, quartz and topaz. Substantial lapidary remains such as raw materials, roughouts, tiny flakes and semi-finished or discarded precious stone artefacts were found in most of the 66 trenches so far excavated at Pattanam. The trench that produced the Sphinx intaglio also produced cameo blanks and debitage of banded agate and other precious stones. In fact, the Sphinx gem is the third intaglio so far found at Pattanam. All the three gems were retrieved from the northern sector of the 70-hectare Pattanam archaeological mound, of which only less than 1 per cent has been excavated so far. The Sphinx gem is made of banded agate, a precious stone belonging to the Indian subcontinent, while the theme or symbol is of Mediterranean genesis.

It is common knowledge now, especially after the excavations at Pattanam and other contemporary sites, that gem and cameo engravers in the Mediterranean area mostly used Indian precious stones. It is also clear that the artist who made the Sphinx was working within the Graeco-Roman tradition of gem carvers. But whether s/he was from the Mediterranean region or from the Indian subcontinent is difficult to confirm. For the figure to have been carved by the fingers of an Indian craftsperson there would have had to be some cultural “amalgamation” between the Indian and Graeco-Roman cultures. Considering the evidence of lapidary remains at Pattanam, the possibility of a Tamilakam artist carving the Sphinx at a Pattanam workshop cannot be ruled out.

DNA and radiocarbon analysis of bone samples from Pattanam validates the idea of a cultural admixing at the Pattanam site 2,000 years ago. These tests and analyses were done by the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) in Hyderabad, India, and the Centre for Applied Isotope Studies (CAIS) at the University of Georgia in the United States. DNA was extracted from 11 samples and when their mitochondrial DNA was sequenced and matched with the DNA database of modern human beings across the world, these individuals were revealed to have belonged to very different regions and cultures. Four were from South Asia, four from Eurasia and three from the Western European region. To borrow a usage, Pattanam was the “cultural rain-forest” of the Old World; an ancient cosmopolitan centre in its population mix.

Sphinx: Story and Origins

But what exactly is a Sphinx seal ring, and what does the Sphinx stand for? In a deeper sense it is a difficult question to answer, since it might represent an areligious artistic expression of an indigenous community and a symbol of evolving multipronged power relationships. Otherwise, a seal ring is a finger ring with a seal for leaving an impression on, say, a document or on sealing wax. The Sphinx was a hugely popular character in Mediterranean mythology, with strong links to the city of Thebes in the Boeotian region of Greece which, from 800 BCE onwards, has been known through numerous myths and heroes. In one such myth, the Sphinx, with its home in Cithaeron mountain, was sent to Thebes to devour the Thebans for committing illegal love—in today’s nomenclature, probably non-consensual love.

In Boeotian legends, the Sphinx is referred to as a winged, female creature in relation to either Thebes or the mythological hero Oedipus, who accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby bringing disaster to the city of Thebes.

There is no reference to the Sphinx in Homer, although he refers to two other basic elements of the Boeotian myth, Oedipus’s parricide and incest. The earliest citation of the Sphinx in connection with the Boeotian myth is in the poem “Theogony” by the Greek poet Hesiodus, who lived in the eight century BCE. He used the word “Phix” for the hybrid creature. How the later popular term “Sphinx” originated is obscure. Some authors have thought it as having links to the Egyptian traditions, though this is quite uncertain.

In Greek literature, the Sphinx is always female; the only male reference is by Herodotus, but that was in relation to the male Sphinx he had seen in Egypt. In fact, creatures mixing human with animal features in Greek art were mostly feminine, to underscore their primordial descendance from Mother Earth. The Sphinx is described by the Greek tragic poets as a winged young woman with the body of a lion. The fullest description of the Sphinx is given by Pseudo-Apollodoros in a compendium of Greek mythology, written between the 3rd and 2nd century BCE, as having a woman’s face and breasts, wings, a lion’s body and tail. A few tragedians have replaced some elements of the Sphinx with a dog’s body and snake’s tail—hybrid, double-natured monsters, but without explanation. However, all Greek tragedians emphasise the winged and feminine character of the Sphinx.

Every day, as the story goes, she infested Thebes by seizing and devouring men, mostly young. As an escape offered to her victims, the Sphinx posed a riddle, which was composed on the advice of Muses (goddesses of arts and sciences), referring to three successive phases of human life. She posed the question, what walks in the morning on four feet and at noon with two and in the evening with three? Those who were unable to answer were seized and devoured irrespective of their status and position. The Thebans assembled every day to answer the riddle and get rid of the Sphinx until Oedipus solved the riddle by answering, “Man crawls on all fours as a baby, walks upright in the prime of life, and uses a staff in old age.” The Sphinx then killed herself by jumping from her mountain or, as in some other versions, allowed herself to be killed by Oedipus.

Seal ring of Octavianus (63 BCE to 14 CE)

According to Roman archaeologists and art historians, the Pattanam Sphinx is a gem belonging to a seal ring and can be considered a good quality example of Graeco-Roman carving art. The Pattanam Sphynx is female not only because of the nipples, but because of the hairstyle and the cheeks without beard. Though the myth of the Sphinx is a subject of wide chronological range, the accuracy of the Pattanam gem style and carving technique suggest a chronology between the 1st and the 2nd century CE.

The young Octavianus (later emperor Augustus Caesar) signed using a seal ring with a Sphinx at the beginning of his political career. Octavianus chose the Sphinx as seal ring because of her oracular power to declare the dawn of a new golden age. It was also the symbol of Apollo, the “personal” god of the young heir of Julius Caesar; Octavianus was also believed to be the son of Apollo. Later, as Augustus Caesar, he used to sign with the portrait of Alexander the Great and then with his own portrait; also, Capricorn, his zodiacal sign and also the sign of the first month of the year, January, is a recurrent symbol on gems portraying Augustus. Astrology seems to have played an important role in the power corridors of Rome but certainly so in determining the seal ring of the emperor.

A travelling seal ring?

Perhaps some of these seal rings travelled to the East with their owners, merchants or as merchandise. Raw material was imported in large quantity from the East in the Roman Empire and was worked on by craftsmen who sometimes came from far-off countries where the material originated (for example, red porphyry, quarried in Egypt, were made into statues, columns and architectural lintels, imported to Rome half-worked and finished there by Egyptian craftsmen travelling with them or living in Rome).

Of course, craftsmen having a long familiarity with the raw material quarried in their land of origin (especially when we consider some exceptional cameos produced for the emperor and his court), worked as “foreigners”, sometime slaves or “liberti”, but also as free artisans, having assimilated the Hellenistic-Roman culture, in the West or for a Western committance. In Egypt, at the Hellenistic Ptolemaic court of Alexandria, there flourished a school of gem and cameo engravers, and some of them, after the conquest by the Romans in 31 BCE, moved to work in Rome.

Regarding the gender preference of their use, in the Roman Empire seal rings were worn by men and women, usually with no distinction in the repertory of images between them.

Cultural Admixing

There was immense possibility for cultural blending because Indian and West Asian precious and semi-precious stones were extensively used in the different provinces of the empire—Greece, Syria, Egypt, but especially in Rome and Italy, where the imperial and senatorial committance required high quality work. Some of these gems could have been sold to people and merchants travelling beyond the borders of the Roman Empire for exchanging jewels, gold, silver, glass and precious objects as payment for silk, spices, carved or uncarved precious and semi-precious stones, art works and similar exquisite objects.

The Berenike site, on the Red Sea coast, in Egypt, the destination port for Indian Ocean merchandise, especially that of Muziris, has brought forth a huge volume of artefacts and materials such as teak wood, gems, glass beads, spices of all varieties, including 7.55 kg of black pepper, and bamboo matting in all probability from the Periyar river valley region, including the Idukki high ranges which even today produces the world’s best-quality spices. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that South Asians resided at Berenike, says Dr Steven Sidebotham, the director of the Berenike excavations.

It is worth recalling here the other two intaglios, seals, unearthed at Pattanam, made of carnelian with carved images of a pouncing lion (2010), and Tyche or Fortuna (2014), the Graeco-Roman goddess of good luck. The engravers could have had a different ethnic background, but adopted a common language, that of the Hellenistic-Roman art, where images of sphinxes and lions were known from the 8th century BCE and of Tyche or Fortuna from the 4th century BCE, and they had symbolic meanings. The goddess on the gem from the Pattanam excavations holds not only the cornucopia, the symbol of abundance and richness, but also the rudder, an allusion to the changing nature of the sea and of luck in human life, suggesting her benevolence towards sailors and merchants who relied on her also to escape the dangers of navigation. The lion symbolised courage, strength and kingship, and also death and was a common subject in the Mediterranean, taken from the art of Egypt and West Asia, as no lion ever lived in Italy or Greece or south India. But the artists copied those images from other artefacts; often the animals were taken as prey in Rome and in the empire for the games in amphitheatres.

Identified and excavated in the 21st century, the Pattanam site could be studied, conserved and illumined following advanced scientific protocols, collaborations, transparency, local community participation, civil society ownership and judicious care of the government. PAMA nurtures such a project—Little Heavens are Possible—towards transforming Pattanam village into a knowledge hub and model heritage zone.

The admixing of “indigenous” cultures that throb beneath the Pattanam archaeological mound might carry elements that may help save “the human race from destroying itself and leading the earth to a disaster”.