Wikimedia Commons/Yad VaShem Archive

Wikimedia Commons/Yad VaShem Archive

Nearly 40 Jews volunteered to serve with Britain’s Special Operations Executive behind enemy lines in World War II.

In 1943, the slaughter of millions of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe became frighteningly clear to the rest of the world. But the Allies focused most of their fighting power on targeting German military resources, having neither the interest in nor the ability to enable oppressed Europeans to fight back against their occupiers.

That’s where a small army of volunteer Jewish parachutists came in.

The Jewish Agency, a body dedicated to the establishment of Israel, asked the British government for help in training and sending hundreds of parachutists into Europe to fight the Nazis. Word was sent out to Jewish Palestinian troops serving with British forces and members of the Palmach, a Zionist youth organization.

Only a handful made it to Europe. Even fewer came back alive. This is their story.

Establishing The Jewish Parachutists

Wikimedia Commons/Government Press Office (Israel)

Wikimedia Commons/Government Press Office (Israel)

The majority of the parachutists were young men and women from kibbutzes, or farm-based communes. Some were already serving in the British Army’s Palestine Regiment when the call for volunteers was issued.

In August 1942, a group of women who’d been exchanged for German POWs arrived in Palestine, bringing with them horror stories of what the Nazis were doing to Europe’s Jews. Many had escaped to Israel, which the Jewish Agency saw as a golden opportunity.

These Jews could be specially-trained and dropped back into their European towns to rescue refugees. With first-hand knowledge of local languages, customs, and geography, these volunteers could covertly and efficiently rescue anyone in hiding.

And so, the Jewish Agency hatched an ambitious plan to drop 1,000 parachute-trained special agents over Nazi-torn Europe, where they could make contact with and aid Jewish refugees and resistance groups, spread word of the stalwart Zionist movement, and even trigger a Jewish uprising.

As good as the idea was, it took months of badgering British officials for the idea to get off the ground. Eventually, 250 eager young men and women, many of whom had recently immigrated to Palestine from countries now occupied by the Germans, volunteered.

The Jewish Agency wanted to send them all into the fray, but Britain agreed to commit resources for just a few dozen. They needed their resources for their own operatives, and they feared that a battalion of trained, seasoned commandos could potentially overthrow British rule in Palestine.

However, in exchange for transportation on British planes, the operatives had to promise to prioritize the setting up of radio and telegraph communications, sabotage, and aiding downed Allied Pilots. The agreement was made and the search for volunteers began in earnest.

The Perilous Plan

Wikimedia Commons/National Photo Collection of Israel

Wikimedia Commons/National Photo Collection of Israel

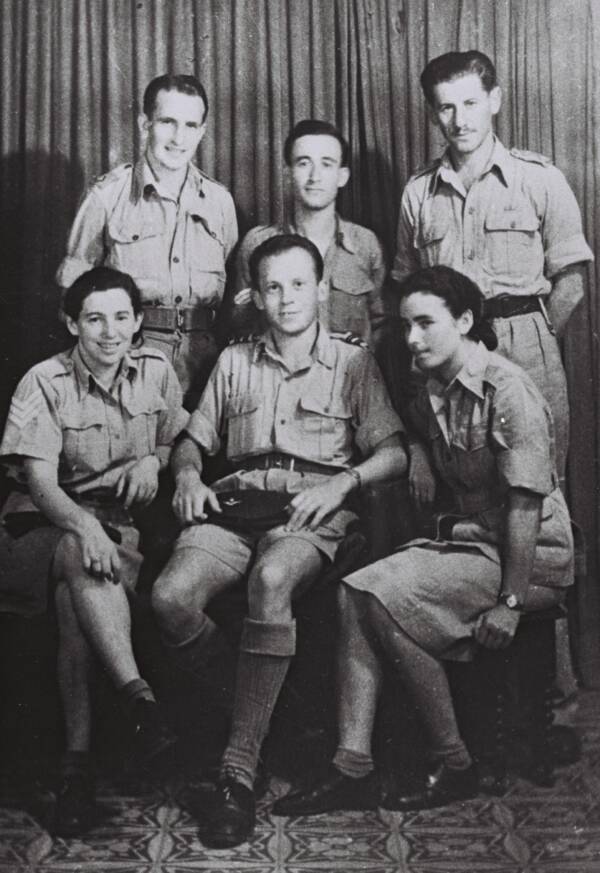

Surika or Sara Braverman, at the bottom left, was the last of the Jewish parachutists to die. Haviva Reik, far right, died in Slovakia in 1944.

Organizing the unit fell to volunteers like Enzo Sereni, an Italian-born former pacifist who’d been active in Zionist circles for about 20 years, as well as the Hungarian-born Yonah Rosen.

As was characteristic of Zionist militant groups like Haganah and Palmach, women were welcome, including the Slovakian-born Haviva Reik and Hannah Szenes, who was from Budapest. Of the 250 initial volunteers, 110 were trained, and the group was further narrowed down to just 37.

British planners also wanted to drop the parachutists solely onto Yugoslavia, where they might link up with Josip Broz Tito’s Partisans, an anti-Axis revolutionary group.

However, the volunteers pointed out obvious deficiencies with this approach, namely that the Partisans controlled only a fraction of Yugoslavia and that dropping all the volunteers in one place increased their risk of capture en masse.

Instead, the Jewish parachutists suggested they take “blind jumps” with teams dropped onto individual countries from the air. As Enzo Sereni argued, “It’s the shortest route and thus the right one. Even if it’s dangerous, with imagination and daring, we can take the enemy by surprise.”

And so they did.

Who Were The Fearless Jumpers

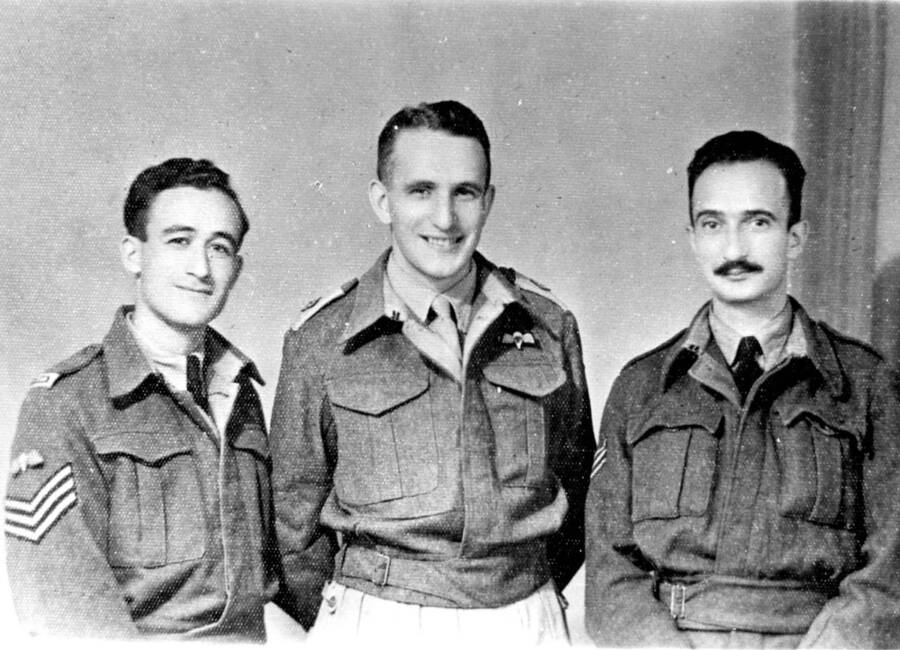

Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museum

Parachuting into Europe was a hazardous affair. Operatives were at risk of being captured and executed as spies if the Germans or their allies found them.

The first jumps began in March 1944. Hannah Szenes’s team was first, dropping into Partisan-held Yugoslavia. But then on March 19, German troops invaded and occupied Hungary, shaking some of the Hungarian-born parachutists’ confidence.

“We were too late,” wrote parachutist Yoel Palgi. “Our hopes of organizing escape and self-defense before the Nazi invasion were dashed. Now we would have to operate under Nazi rule.”

Nevertheless, the jump went ahead. Of those parachutists who’d landed in Yugoslavia, several dispersed to neighboring countries by foot. Palgi met up with Szenes to infiltrate Hungary, where her widowed mother and younger brother were still hiding in Budapest and hadn’t written for weeks by the time she left Palestine.

Haviva Reik, who’d been set to jump with three male parachutists, was pulled from the mission at the last minute as British officers were sure she’d be executed as a spy, since the Germans were unlikely to believe that she was a soldier.

When her comrades made their way to central Slovakia against the backdrop of the Slovak National Uprising, they were surprised to find Reik already there, having talked her way into a separate Allied jump.

In Romania, parachutists moved swiftly and undetected through the Ploiești oilfields to rescue stranded Allied airmen. But their most daring activities would take place just before and after the D-Day invasion.

The Danger Of Life In Occupied Europe

Parachuting into Europe was a hazardous affair. Operatives were at risk of being captured and executed as spies if the Germans or their allies found them.

After the Allies touched down in Normandy, the Soviet Union and its partisan allies turned the tide on the grueling Eastern Front. As such, they operated with minimal support and far from the safety of the Allied armies — but the parachutists knew the risks they faced.

Once on the ground in Slovakia, parachutists Haviva Reik ran rescue operations and a soup kitchen for Jewish refugees, which she organized into a functional resistance group. But then on Nov. 20, 1944, Reik was captured and killed along with nearly 1,000 others in the Kremnička massacre.

Hannah Szenes, Yoel Palgi, and their comrade Peretz Goldstein were arrested soon after their arrival in Hungary. In prison, Szenes was tortured before reuniting with her mother, who was brought in by interrogators to intimidate her. She refused to tell her captors any details of her mission.

After a sham trial, Szenes was executed by firing squad on November 7. Peretz died in Oranienburg concentration camp, while Palgi escaped from a train while in transit and assisted Allied air crew in Romania until the Red Army liberated the country.

In total, 12 of the 32 parachutists who entered Axis-held countries were captured. Seven died. The majority were active until Allied forces reached them, playing a vital and often-forgotten role in the defeat of fascism.

The Triumphs Of The Jewish Parachutists

Haviva Reik’s death at the hands of Germans and Slovak collaborators made her a martyr for Palestine’s Jews.

The sacrifices of the Jewish parachutists became legendary in postwar Palestine. Hannah Szenes’s death made her a martyr to the Yishuv, the Palestinian Jewish community before the establishment of the state of Israel.

Haviva Reik’s remains were transferred from a mass grave in Slovakia to a military cemetery in Israel, and her name graces streets throughout the country. Reuven Dafni was decorated for his service and returned to Palestine, where he and Palgi raised funds for the establishment of the Israeli military in 1948.

For a generation of Jews who’d lost friends, family, and whole communities to the brutality of the Nazi regime, figures like the parachutists were a powerful symbol of resistance.

In 2013, the last of the volunteers, Surika Braverman, died at the age of 95. As she put it, she and her fellow operatives were “not leaders, just normal people.”

“You have to understand, we didn’t go to Europe to overthrow the Third Reich,” Braverman said. “We didn’t think they would make of us heroes, we wanted to go to the Jews of Europe and say that we had come to help.”