Ministers meeting here in Milan at the final UN session before the Glasgow COP26 climate conference heard that some progress was being made.

But officials from developing countries demanded tougher targets for cutting carbon emissions and more cash to combat climate change.

One minister condemned "selfishness or lack of good faith" in the rich world. US special envoy John Kerry said all major economies "must stretch" to do the maximum they can.

Money on the agenda at Milan climate talks

Youth have right to be angry on climate, UK PM says

Australia PM may skip COP26 climate summit

Around 50 ministers from a range of countries met here to try to overcome some significant hurdles before world leaders gather in Glasgow in November. But for extremely vulnerable countries to a changing climate the priority is more ambitious carbon reductions from the rich, to preserve the 1.5C temperature target set by the 2015 Paris agreement.

Scientists have warned that allowing the world temperatures to rise more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels is highly dangerous.

An assessment of the promises made so far to cut carbon suggests that the world is on track for around 2.7C. Ministers from developing countries say this is just not acceptable - they are already experiencing significant impacts on their economies with warming currently just over 1C. "We're already on hellish ground at 1.1C," said Simon Steill, Grenada's environment minister who argues that the plans in place just weren't good enough to prevent disaster for his island state.

"We're talking about lives, we're talking about livelihoods, they cannot apply smoke and mirrors to that."

"Every action that is taken, every decision that is taken, has to be aligned with 1.5C, we have no choice."

Some delegates felt that richer countries aren't sufficiently engaged on the issue of 1.5C, because they are wealthy enough to adapt to the changes.

"They don't care about 1.5C because if there's sea level rise, they have the means to build sea walls, and they are just remaining there in their high walls of comfort," said Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

"Some countries are willing to do things but they don't have the means, some have the means but are not willing to do things. Now how do we find the right choreography?"

On this question of choreography, ministers were in agreement that the G20 group of countries should be leading the dance. Mr Kerry called on India and China, who are part of the G20, to put new carbon plans on the table before leaders gather in Glasgow.

"All G20 countries, all large economies, all need to try to stretch to do more," he told the gathering.

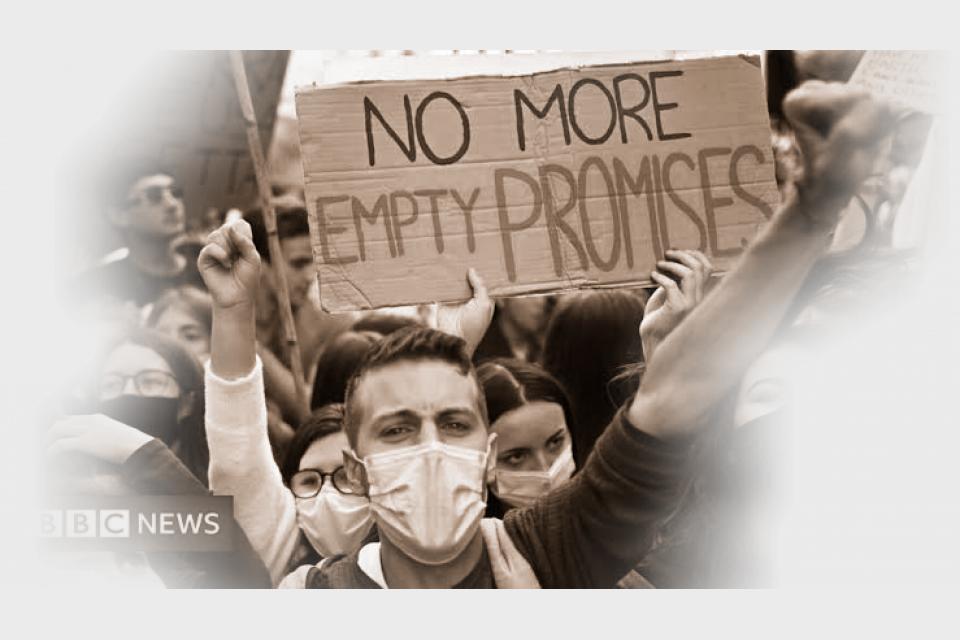

"I'm not singling out one nation over another. But I am encouraging all of us to try to do the maximum we can." The mood on the street in Milan could not have contrasted more sharply with the formal, political roundtable discussions inside the PreCOP26 conference.

On Friday, students and activists marched to the doors of the conference venue - banners waving and arms linked in a human wall to protect Greta Thunberg, who led the procession. There were cheers of: "We are unstoppable, another world is possible". And just one day after sharing the stage with world leaders, and after meeting the Italian prime minister, 18-year-old Greta told a cheering crowd: "We are sick of their blah blah blah and sick of their lies."

Meanwhile, behind the concrete walls of the conference hall on Saturday, ministers were cautiously optimistic that their discussions had laid crucial foundations for the UN climate meeting in November. As he brought the meeting to a close, Alok Sharma, president for the much-anticipated COP26 in Glasgow, assured me that there was now a tangible "sense of urgency".

"It's this set of world leaders that are deciding the future," he said. "We're going to respond to what we've heard here from young people." One of the biggest remaining hurdles to progress remains the question of finance. The richer world promised to pay developing nations $100bn a year from 2020.

That figure hasn't yet been met and while ministers here were confident it would be achieved in Glasgow, the failure to land the money is eroding trust.

"Everything we need to do, we know what that is, and now it's just a question of who's going to be paying for it, who is going to be willing to share their technology," said Tosi Mpanu Mpanu.

"And that's where the problem is. So there seems to be at times selfishness or lack of good faith." Despite these reservations, the UK minister tasked with delivering success in Glasgow was in positive mood after the meeting in Milan.

"I think we go forward to Glasgow with a spirit of co-operation," said Alok Sharma.

"I do not want to underestimate the amount of work that is required but I think there is a renewed urgency in our discussions."

However there are significant hurdles to clear before leaders arrive in Glasgow and technical questions about carbon markets and transparency are still unresolved.

"We need to change. And we need to change radically, we need to change fast," said EU vice-president Frans Timmermans. "And that's going to be bloody hard."